In my last post we explored the nuts and bolts of how neural networks work by building a simplified neural net using nothing but numpy and Python.

We’ll build a neural network with Tensorflow and teach it to be able to classify images of hand written numbers from 0-9 using the MNIST dataset.

We’ll start by importing Tensorflow and downloading our dataset which is included in Tensorflow for us…

Our dataset

import tensorflow as tf

# Download the mnist dataset and load it into our mnist variable, we'll use one hot encoding...

from tensorflow.examples.tutorials.mnist import input_data

mnist = input_data.read_data_sets("MNIST_data/", one_hot=True)

We’ll use one hot encoding which means we’ll convert classifications to a combination of 0’s and 1’s to represent our classification. For example, we could say that True becomes [0,1], and False becomes [1,0], or Cat becomes [1,0,0], while Dog and Mouse become [0,1,0] and [0,0,1] respectively.

In our dataset, the position of the 1 will reflect which number it is from 0-9. For example [0,0,0,1,0,0,0,0,0,0] would represent 3 as it is in the third position (counting from 0).

Our mnist variable will hold the MNIST data which is split into three parts for us:

- Train (55,000 data points of training data accessible via

mnist.train) - Test (10,000 points of test data accessible via

mnist.test) - Validation (5,000 points of validation data accessible via

mnist.validation)

Train/Test/Validation splits are very important in machine learning. They allow us to keep back a portion of data to test the performance of our model on data it hasn’t seen before for a more reliable accuracy rating. The validation split we won’t use here, but this is usually reserved as a dataset with which to compare the performance of different models, or the same model with different parameters in order to find the best performing model.

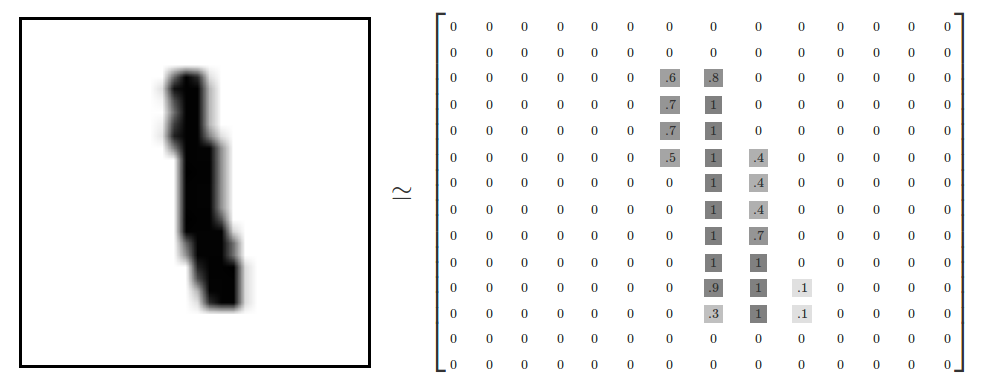

Let’s take a look at our data…

Forward Propagation

Tensorflow works by having you define a computation graph for your data to flow through. You can think of this as like a flow chart; data comes in at the top, and each step we perform an operation and pass it to the next step. Once we’ve defined this in Tensorflow, we can then run it as a session. Tensorflow is great at being able to spread this out across GPUs and other devices for faster processing too should we need it.

As we need to define the computation graph beforehand, we need to create Placeholders which are special variables in Tensorflow that accept incoming data. They’re the gateways to putting data into our neural network. We’ll need two, one to input our dataset of images, and one to input the correct labels. The placeholder for our dataset of images will become the input neurons at the front of our neural network…

# We'll input this when we ask TF to run, that's why it's called a placeholder

# These will be our input into the NN

# None means we can input as many as we want, 748 is the flattened array of our 28x28 image.

inputs = tf.placeholder(tf.float32, [None, 784]) # Our flattened array of a 28x28 image

labels = tf.placeholder(tf.float32, [None, 10]) # Our label (one hot encoded)

Next, we’ll define and initialise our weights and biases…

# Initialise our weights and bias for our input layer to our hidden layer...

# Our input layer has 784 neurons! That's one per pixel in our flattened array of our image.

W1 = tf.Variable(tf.random_normal([784, 300], stddev=0.03), name='W1')

b1 = tf.Variable(tf.zeros(300), name='b1')

# And the weights connecting the hidden layer to the output layer...

# We pass our 784 input neurons to a hidden layer of 300 neurons, and then an output of 10 neurons (for our 0-9 classification)

W2 = tf.Variable(tf.random_normal([300, 10], stddev=0.03), name='W2')

b2 = tf.Variable(tf.zeros(10), name='b2')

Biases are just like another set of neurons to give us a little more variance to tune in our network. Just like before, we’ll pass our inputs through the first layer, multiplying our weights and adding a bias. Then we’ll apply an activation function. This time we’ll use a RELU activation function instead of the sigmoid we used previously (RELU’s are the trendy activation function right now). Our final prediction will be activated using a softmax function which will convert our prediction to between 0 - 1 for our output.

hidden_out = tf.add(tf.matmul(inputs, W1), b1)

hidden_out_activated = tf.nn.relu(hidden_out)

output = tf.add(tf.matmul(hidden_out_activated, W2), b2)

predictions = tf.nn.softmax(output)

Backpropagation

We’ll define our cost function next, this is where things start to get a little easier by using Tensorflow. As Tensorflow has gone through our forward prop, it automatically knows how to do backprop! We just have to define which cost function we’ll be using and how we want to minimise it.

cross_entropy = tf.reduce_mean(-tf.reduce_sum(labels * tf.log(predictions), reduction_indices=[1]))

We’ll need to define our hyperparameters. Hyperparameters are like the tuning knobs of neural network, they’re various parameters that control things like how fast our network will learn and end up affecting the final accuracy of our network. They’re called hyperparameters as they’re the parameters that affect how our network learns its parameters (the optimal weights and biases).

learning_rate = 0.5

epochs = 1000

batch_size = 100

Instead of calculating the gradients ourselves like last time, Tensorflow let’s us just specify which way we’ll be optimising our algorithm. We’ll use Gradient Descent like last time, although there are other options available to us which do the same minimizing of a cost function in different ways. We’ll specify gradient descent as the way we’re optimising, and then give it the cost function we want to minimise using gradient descent.

optimiser = tf.train.GradientDescentOptimizer(learning_rate=learning_rate).minimize(cross_entropy)

Training

We have to initialise the variables we defined in Tensorflow. We’ll also come up with a way to accurately measure how if our prediction was correct…

init = tf.global_variables_initializer()

# Define an accuracy assessment operation

correct_prediction = tf.equal(tf.argmax(labels, 1), tf.argmax(predictions, 1))

accuracy = tf.reduce_mean(tf.cast(correct_prediction, tf.float32))

Finally we can run our Tensorflow session and train our network. After our training loops, we’ll pass in the unseen test dataset to see how well our network did.

with tf.Session() as sess:

sess.run(init)

for epoch in range(epochs):

batch_xs, batch_ys = mnist.train.next_batch(100)

sess.run(optimiser, feed_dict={inputs: batch_xs, labels: batch_ys})

print(sess.run(accuracy, feed_dict={inputs: mnist.test.images, labels: mnist.test.labels}))

0.9682

A 0.9682% accuracy isn’t awful for our first network! But this can be improved quite easily. Try tuning the network above to see how you can increase performance. You may want to try tweaking the hyperparameters, changing the activation functions or optimiser. The best algorithms can get over 99% accuracy on this task!